Those Who Came: Journal from AFSC Voter Registration Project SOUTH CAROLINA JUNE 22 - JULY 8, 1966

BY: ABBY YOUNG

“We are the children of tomorrow

We pray for our lives

Our loves

Our time of being

Make peace, our fathers, make peace.”

Written on the wall of Operation Bootstrap Community Center in Watts, Los Angeles, 1965

We pray for our lives

Our loves

Our time of being

Make peace, our fathers, make peace.”

Written on the wall of Operation Bootstrap Community Center in Watts, Los Angeles, 1965

Preface

Abby Young, Louie Dicks, our local representative and volunteer from Sumter, Jim Churchill from Pomona College, and various neighborhood children in front of the Sumter Parsonage.

Abby Young, Louie Dicks, our local representative and volunteer from Sumter, Jim Churchill from Pomona College, and various neighborhood children in front of the Sumter Parsonage.

A powerful Civil Rights Conference held during my freshman year at Pomona College brought major African American leaders from the South to speak to our primarily white campus in Claremont, California. The year was 1963 and these leaders were traveling the country to bring stories from the South and the Civil Rights Movement to students and the wider public. Their stories of courage and spirit in the face of hatred and violence shattered my sheltered upbringing and uprooted me overnight.

I became active in the in the Civil Rights Movement from that time on, working in the urban African American communities in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and focusing my college studies on Race, Black History, and Social Change. But I had never been to the South. A friend working with the Movement in Georgia encouraged me to come. I knew from his letters how difficult and dangerous this work was.

In 1964, “Freedom Summer” took place in the South, with the goal of registering African Americans to vote and beginning to break down institutionalized racial barriers. This was the summer when students from all over the rest of the country began to go South to join the struggle. But there was a high price to pay.

Racial violence had a long and ugly history in the South, and dismantling this system was not going to come without a fight. That summer, a group of black and white civil rights workers were brutally murdered in Mississippi––James Earl Chaney from Meridian, Mississippi, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner from New York City. Outrage over the activists’ disappearances magnified the already intense conflict and struck deeply at the conscience of the nation.

The courageous sacrifices of many during this turbulent time helped fuel the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

I knew it was time to do my part. So in the summer of 1966, as a 20-year old college student, I left for Sumter, South Carolina to join a Voter Registration Project sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee. I kept a journal during the short time I was there, and excerpts from that time are remembered here.

*Historically there have been many forms of usage to address the evolving sensibilities and realities on the issue of race in America—and rightly so. In 1966, at the time of this journal, the terms “black” and “white” were in current use, often without capitalization. I have retained this usage here to reflect the particular moment in time, but this choice is also open to change as we all change together.

I became active in the in the Civil Rights Movement from that time on, working in the urban African American communities in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and focusing my college studies on Race, Black History, and Social Change. But I had never been to the South. A friend working with the Movement in Georgia encouraged me to come. I knew from his letters how difficult and dangerous this work was.

In 1964, “Freedom Summer” took place in the South, with the goal of registering African Americans to vote and beginning to break down institutionalized racial barriers. This was the summer when students from all over the rest of the country began to go South to join the struggle. But there was a high price to pay.

Racial violence had a long and ugly history in the South, and dismantling this system was not going to come without a fight. That summer, a group of black and white civil rights workers were brutally murdered in Mississippi––James Earl Chaney from Meridian, Mississippi, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner from New York City. Outrage over the activists’ disappearances magnified the already intense conflict and struck deeply at the conscience of the nation.

The courageous sacrifices of many during this turbulent time helped fuel the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

I knew it was time to do my part. So in the summer of 1966, as a 20-year old college student, I left for Sumter, South Carolina to join a Voter Registration Project sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee. I kept a journal during the short time I was there, and excerpts from that time are remembered here.

*Historically there have been many forms of usage to address the evolving sensibilities and realities on the issue of race in America—and rightly so. In 1966, at the time of this journal, the terms “black” and “white” were in current use, often without capitalization. I have retained this usage here to reflect the particular moment in time, but this choice is also open to change as we all change together.

June 22, 1966

|

Why we are compelled to go South right now is somewhat of a mystery to me. But still thank God, we do. I question whether it is my place as a white Northerner to interfere. I think it is.

So I’m on my way to South Carolina to take part in an American Friends Service Committee voter registration project and take part in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. |

I was making a promise to myself at that time—a promise that I wouldn’t forget the hurt and the pain of racism that I had just been confronted with, and that had shattered my view of the world. |

Sure I’m afraid, given all that has happened up to now. But afraid of the strangest things. I’m afraid of the raw-boned reality I’m going to meet. I’ll see people hurting, and I know that will be the hardest. But I’m driven to go.

As I saw the sun rise from the plane window this morning, I watched it color the sky. It came slowly barreling up, and I looked straight into its molten light.

I remembered then how I had stared into this same sun one late afternoon as a freshman at Pomona College, just after the Civil Rights Conference had ended. The sun was burning my eyes, but I stared into it grimly, making the promise that I would never forget the hurt and the pain of racism that I had just been confronted with––that had shattered my view of the world. And so I remembered that promise this morning and was glad.

As I saw the sun rise from the plane window this morning, I watched it color the sky. It came slowly barreling up, and I looked straight into its molten light.

I remembered then how I had stared into this same sun one late afternoon as a freshman at Pomona College, just after the Civil Rights Conference had ended. The sun was burning my eyes, but I stared into it grimly, making the promise that I would never forget the hurt and the pain of racism that I had just been confronted with––that had shattered my view of the world. And so I remembered that promise this morning and was glad.

June 23 , Columbia, S.C.

|

Coming into the airport in Columbia, I asked a soldier on the plane if any of those guys on the plane were going to Vietnam. “Coming back,” he said. Suddenly I don’t feel heroic at all.

It’s hot in Columbia. Eleven of us are staying overnight with a local couple, Sharon and Dick Miles, in their four-room apartment. Our hosts are warm and welcoming, and no one seems to mind that it is pleasantly chaotic. Our project leaders from the American Friends Service Committee for the summer are Bob and Margaret W. They have a baby nicknamed Squeaky. Squeaky is part of our project too. |

As each member of the group arrives, I feel an underlying energy and spirit. The Movement is something visceral. It is a Movement-Toward. It is beautiful and young and brave, and we are all inexorably drawn by its magnetism. We have all sacrificed something to come. |

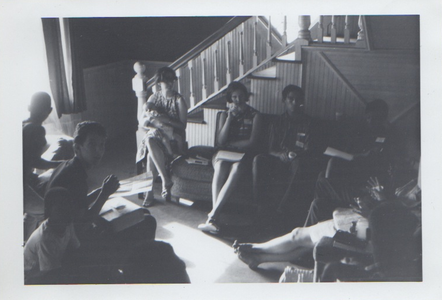

There are nine of us white volunteers arriving tonight from around the country, and four more volunteers from black Southern colleges and universities will join us when we arrive in Sumter. Some of the group here have prior experience with the Peace Corps, Job Corps, tutoring inner city kids, or living in the South, but none of us really knows what is going to happen this summer.

As each member of the group arrives, I feel an underlying energy and spirit. We have all sacrificed something to come. The Movement is beautiful and young and brave. It is something visceral, and we are all drawn by its magnetism.

As each member of the group arrives, I feel an underlying energy and spirit. We have all sacrificed something to come. The Movement is beautiful and young and brave. It is something visceral, and we are all drawn by its magnetism.

June 24, COLUMBIA, S.C.

We had orientation today. A VISTA leader from North Carolina, Charles Webster, spoke to us about “moderate progress.” A young woman, Edna Smith, told us about her work with the “Speed-Up” Program for early childhood education. An older woman, Mrs. Libby Dean, gave a talk about her experience working to integrate and improve local schools for over twenty years.

From what I learned today, a huge sea change has been rumbling below the surface for decades, challenging and confronting racist practices. At depth, the rumbling barely seems to break a ripple on the surface. But now, I am part of the rumbling, joining in with those who are moving and changing things from below. Up on the surface, the image shivers.

Later, after dinner, we went to our first party as a mixed group. Lots of uneasy talk. It’s a strange world here. I feel completely raw–but ready for whatever comes.

From what I learned today, a huge sea change has been rumbling below the surface for decades, challenging and confronting racist practices. At depth, the rumbling barely seems to break a ripple on the surface. But now, I am part of the rumbling, joining in with those who are moving and changing things from below. Up on the surface, the image shivers.

Later, after dinner, we went to our first party as a mixed group. Lots of uneasy talk. It’s a strange world here. I feel completely raw–but ready for whatever comes.

June 24, Sumter, S.C.

We left Columbia and headed for Sumter early in the afternoon. Already we’re impatient to get there. I saw the swamps go by, then miles and miles of trees. But how come every car looks so sinister? The hair bristles involuntarily on the back of my neck. I smell violence in the land—maybe not for me—but it’s in the land, and I shudder at it.

Sumter is a small town. Its one main street has many shops, with side streets that are filled and busy. Out past town we went, over the tracks and into the black part of town.

Sumter is a small town. Its one main street has many shops, with side streets that are filled and busy. Out past town we went, over the tracks and into the black part of town.

We are staying in the parsonage of the Second Presbyterian Church. It has been loaned out to us for the whole summer. Sunday School classes had to move to the basement of the church next door, but that’s all right, they tell us. As we arrived, the neighborhood children were immediately around us and shyly underfoot, saying yes ma’am, yes sir to us all—a new experience for me. I felt very awkward and yet so glad just to be here. The ladies of the church came over to bring us supper, each one coming in with a wide smile, carrying a dish. We shook hands up and down, smiling and saying our names over and over. They brought us a true feast: potato salad, fried chicken, sherbet, mints, cookies, and koolaid. The children still couldn’t get over us. After dinner, we played ball and laughed together––getting used to each other.

The house we will be staying in is a two-story parsonage. It has bulky furniture, plaster coming off the walls and ceilings, and Sunday School signs still on the walls. The women will all share one bedroom, and the men another. It looks big and beautiful to me. Gathering for our first group meeting, our project leader Bob told us that the Quaker Friends practice what is known as “searching for the truth.” That means you need to hear each person’s say and put yourself inside each person’s skin and listen. And just as all the voices in our own group need to be heard before making any decisions, so we need to hear and consider the voices of all those we will be meeting on the outside.

The house we will be staying in is a two-story parsonage. It has bulky furniture, plaster coming off the walls and ceilings, and Sunday School signs still on the walls. The women will all share one bedroom, and the men another. It looks big and beautiful to me. Gathering for our first group meeting, our project leader Bob told us that the Quaker Friends practice what is known as “searching for the truth.” That means you need to hear each person’s say and put yourself inside each person’s skin and listen. And just as all the voices in our own group need to be heard before making any decisions, so we need to hear and consider the voices of all those we will be meeting on the outside.

June 26, Sunday, Sumter

I went to Mount Pisgah AME church with Louie D., a Sumter resident and one of our local leaders. Reverend F.C. James, was presiding. The congregation sang harmonies that surged and fell, and then gathered to swell again:

Lord I want to be Christian

In my heart, in my heart.

Lord, I want to be more loving

In my heart, in my heart.

Later in the service, Reverend James introduced Louie and me and gave our summer project a pitch. Heads turned throughout the church. That evening we went to a mass meeting at a school gym in Clarendon County in support of Reverend Hunter who is in a run-off election tomorrow. He is running again for the South Carolina House of Representatives, after losing the first election by only 69 votes to a white opponent. People stared at us white newcomers. A woman held my hand tightly as I beamed into her face. She said, “You know, it’s not often we see such a friendly face.”

One of the speakers told this story:

“A mother,” he said, once lost her son in the wheat fields. She did not know what to do. She called her neighbor and together they went through that field looking for the child. But night fell and still they could not find him. The mother returned home, her heart heavy. That night she prayed to the Lord. And the Lord that night whispered in her ear: ‘Tomorrow, go forth, and call all your neighbors from all around. Then you all join hands and walk through that wheat field, till you find the lost child.’

So early the next morning, the mother rose and she called together all her neighbors from all around. Then they joined hands and together walked through the field. And suddenly one of them cried ‘I have found the child!’ And there was great rejoicing.”

When the story ended, the speaker said, “We must all join hands till we find that child.” Those of us who have come from so far have also come to find that child.

Lord I want to be Christian

In my heart, in my heart.

Lord, I want to be more loving

In my heart, in my heart.

Later in the service, Reverend James introduced Louie and me and gave our summer project a pitch. Heads turned throughout the church. That evening we went to a mass meeting at a school gym in Clarendon County in support of Reverend Hunter who is in a run-off election tomorrow. He is running again for the South Carolina House of Representatives, after losing the first election by only 69 votes to a white opponent. People stared at us white newcomers. A woman held my hand tightly as I beamed into her face. She said, “You know, it’s not often we see such a friendly face.”

One of the speakers told this story:

“A mother,” he said, once lost her son in the wheat fields. She did not know what to do. She called her neighbor and together they went through that field looking for the child. But night fell and still they could not find him. The mother returned home, her heart heavy. That night she prayed to the Lord. And the Lord that night whispered in her ear: ‘Tomorrow, go forth, and call all your neighbors from all around. Then you all join hands and walk through that wheat field, till you find the lost child.’

So early the next morning, the mother rose and she called together all her neighbors from all around. Then they joined hands and together walked through the field. And suddenly one of them cried ‘I have found the child!’ And there was great rejoicing.”

When the story ended, the speaker said, “We must all join hands till we find that child.” Those of us who have come from so far have also come to find that child.

June 28, Sumter, Manning

This morning nine of us picked up and went to Manning to help bring in voters for Rev. Hunter’s election today. We arrived at the AME church early and sat around impatiently. It was our first day of canvassing and we were all excited to get going.

My first assignment was to visit two neighborhoods with three young girls from the community--Rosalie, Bertie, and Celestine--each about fourteen. We walked along quietly together.

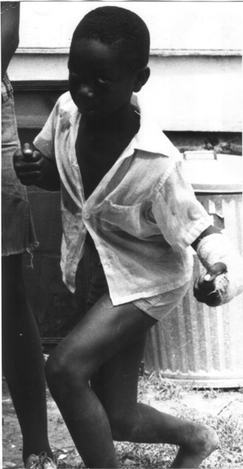

What I saw that first day was difficult to absorb—unpaved dirt roads, small shacks, dusty gardens, gates and fencing falling down. And everywhere, children—clinging to their mothers, peering up at us, or hiding behind doorways. Got a few stares from white men driving by too. Lingering and piercing.

The first lady we went up to was sitting on her porch, swinging back and forth in her chair. “Ma’am,” said one of the young girls, “have you voted today?” She shook her head slowly. “Are you registered yet, Ma’am?” Again, she shook her head slowly “Ain’t going to.” We thanked her and walked on.

Back at the AME church I met Barbette B. and Brenda B. who had volunteered to help us canvas. They are both just sixteen and told me they have done “much of this kind of thing” before. Brenda has a great, quick smile, and she and I started talking shyly. After a while, she told me about some of her experiences—the guys being beaten, the girls being terrorized, how she’d lost a tooth “doing this kind of stuff,” and how she figured if she was going to die, she was going to die. I was stunned by her courage and her story.

We went out to lunch, Brenda, Babette, and me. We stood waiting and talking outside the window of the take-out place amid stares and stalling from the white staff inside. The three of us were all very much aware of the stalling. When we left, Brenda and Babette giggled. What relief there is in laughter.

That afternoon, I drove into the country with Rosalie, Bertie, and Celestine. We were going to pick up a lady so she could come into town to vote. Several young white boys about the same age as my companions were standing by the polling place as we arrived, and stared at us very coldly. As we left, they came out on the steps and jeered, flipping us the bird and mouthing “Fuck you, you bitch.” The young girls replied in kind!

We drove on to Sommerton and stopped at a polling place. One elderly man who could barely walk was led in carefully by one of the poll-watchers. He came out with a gentle smile. He didn’t know where to go, so headed off in the wrong direction. The poll-watchers gently guided him back. He was radiating pride. Tears came to my eyes. I stayed watching the voting until a policeman told me to leave. I was evidently smiling too broadly myself.

My first assignment was to visit two neighborhoods with three young girls from the community--Rosalie, Bertie, and Celestine--each about fourteen. We walked along quietly together.

What I saw that first day was difficult to absorb—unpaved dirt roads, small shacks, dusty gardens, gates and fencing falling down. And everywhere, children—clinging to their mothers, peering up at us, or hiding behind doorways. Got a few stares from white men driving by too. Lingering and piercing.

The first lady we went up to was sitting on her porch, swinging back and forth in her chair. “Ma’am,” said one of the young girls, “have you voted today?” She shook her head slowly. “Are you registered yet, Ma’am?” Again, she shook her head slowly “Ain’t going to.” We thanked her and walked on.

Back at the AME church I met Barbette B. and Brenda B. who had volunteered to help us canvas. They are both just sixteen and told me they have done “much of this kind of thing” before. Brenda has a great, quick smile, and she and I started talking shyly. After a while, she told me about some of her experiences—the guys being beaten, the girls being terrorized, how she’d lost a tooth “doing this kind of stuff,” and how she figured if she was going to die, she was going to die. I was stunned by her courage and her story.

We went out to lunch, Brenda, Babette, and me. We stood waiting and talking outside the window of the take-out place amid stares and stalling from the white staff inside. The three of us were all very much aware of the stalling. When we left, Brenda and Babette giggled. What relief there is in laughter.

That afternoon, I drove into the country with Rosalie, Bertie, and Celestine. We were going to pick up a lady so she could come into town to vote. Several young white boys about the same age as my companions were standing by the polling place as we arrived, and stared at us very coldly. As we left, they came out on the steps and jeered, flipping us the bird and mouthing “Fuck you, you bitch.” The young girls replied in kind!

We drove on to Sommerton and stopped at a polling place. One elderly man who could barely walk was led in carefully by one of the poll-watchers. He came out with a gentle smile. He didn’t know where to go, so headed off in the wrong direction. The poll-watchers gently guided him back. He was radiating pride. Tears came to my eyes. I stayed watching the voting until a policeman told me to leave. I was evidently smiling too broadly myself.

June 29, Sumter

|

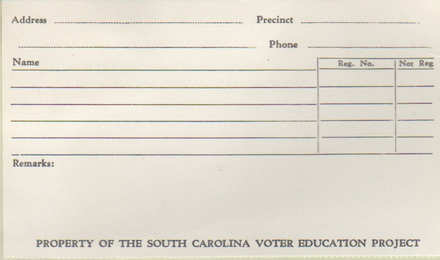

Today was our first day of canvassing for registration in Sumter. Hot dusty roads all morning. Three and a half hours a day is all we do, and yet the time can seem unending. The proportions of the task finally struck me. This is going to be hard, daily, grinding work. Our initial contacts with people are so sketchy and superficial it is frustrating. But registration is just the beginning. There is so much more to do.

Roy G., one of our Southern university members, organized the group for the day. I was paired with Bill W. and we set off on our routes. The first lady we met was agreeable and ready to register. We were surprised and excited. The lady at the next house wouldn’t talk to us or give us her name. Another said apologetically “I lost my Bible and I can’t remember how old I am.” |

We drove on to Sommerton and stopped at a polling place. One elderly man who could barely walk was led in carefully by one of the poll-watchers. He came out, suppressing his pride and his grin. He didn’t know where to go, so headed off in the wrong direction. The poll-watchers gently guided him back. He was solitary and radiant. Tears came to my eyes. I stayed watching the voting until a policeman told me to leave. I was evidently smiling too broadly myself. |

At one stop, two ladies saw us coming, and tried to avoid us by going around to the back of their house. But we persevered and went around back to find them. They jumped when they saw us, but after we talked, we all laughed together.In the end, we made appointments to pick up about six people after having canvassed two blocks of thirty people. Attorney Finney, our local project mentor, says that to get a 30% response, we are doing well.

June 30, Sumter

|

Canvassing in the afternoon today, we met an 80-year old lady named Mary Davis. At first, she protested about registering, saying she had arthritis, she was deaf, she couldn’t read. I was sitting close to her, listening intently to what she was saying. At a certain point, she looked at me and somehow we connected. She then turned slowly, and said querulously, “Next Tuesday?”

|

We were so happy we felt like flying. We promised her a wheelchair, strong men to roll her in it, and the world. |

We were so happy we felt like flying. We promised her a wheelchair, strong men to roll her in it, and the world.When we go out in the afternoon, the mornings free but I never know quite how to use them. The neighborhood children are always around and yearning for something to do. Putting a program together for them would be a full-time job though. Right now we simply don’t have the time. But I’m working on it.

July 1, Sumter

We had a good group meeting at the house today in which we finally hashed out some questions that have been creating tension for us. Why we are here? Is it just to register people and leave it at that? Or do can we use our canvassing to find out the larger needs of the community and then help them follow up?

The superficial approach of canvassing has been bothering me considerably because it does not address the larger issues we run into daily. We finally decided to find out what other concerns the community has in areas like welfare, housing, and public health. Then we will see if we act on it together.

Another new thing is in the air: I asked the kids what activities they would like to do, and they started spouting ideas on every hand—plays, painting, dancing, drawing, and more. So for starters, after lunch Jim C. and I, led by a band of about twenty children, headed for the nearby community center to see if we could use it for some activities. As we walked across the highway to check things out, the children were happily chattering and leaping around in excitement.

The park is not big or even nice. There is broken glass all over, with broken swings and a broken spinning platform. The children didn’t seem to mind and just swarmed all over the equipment, laughing, shouting, and yelling.

I was surprised to see white children playing there too. They were part of a group of about ten white people, led by a heavy-set lady and accompanied by a few teen-agers. “They never talk to us,” said our kids. After a while their group retreated to huddle in the shade of a tree from which they watched us.

Jim went over to them. I played on with our kids, but suddenly it was tense. We didn’t know what would come next. Finally I too went over to the group, and the children followed. Once under the tree together, all the children in our group pressed close to Jim and me, absolutely still and silent.

Jim was talking quietly with the lady:

The lady: “We believe it ain’t Christian to mix them.

Jim: Christ never said that.

The lady: Well, he made them the color they are. Just tell us when you’re going to bring them and we’ll know what to do. We can’t have our children wading in the same pool with them, you understand.

Jim: Ma’am, they have as much a right to wade as your children. And they are simply full of energy and must get it out.

The lady: Stony Hill, down the road, that’s for colored.

Jim: That’s too far, Ma’am.

The lady: Has all the same facilities.

Jim: Have you ever been there?

The lady: No. That’s the colored section. Now this is for white. White people made this and painted it. Just tell us when you’re going to come and we’ll know what to do.

Jim: We can’t stop them, Ma’am.

The lady: (astonished) Well, you brought them here. You brought them here—holding two of them by the hand!

Jim (quietly): It’s a new day.

One of the teenagers muttered: Not until I die.

The lady: We wouldn’t hurt them for the world, see—we just don’t want them around our kids.”

The strange thing is that, when confronted with each other face to face, we were all abashed. All of us. Our two groups sat and talked quietly together. Entrenched, but for a moment at least, speaking. And no one was exploding––no one––from the extended contact.

Our group played quietly a while longer and then left. We must go back.

This afternoon I went canvassing with Hammie Lee J. as my guide. He is thirteen and has a sharp and comic wit. I was glad to be paired with him—my contact, my friend, my guide. We came to a small one-room shack with advertisements hung on the patchwork boarding. We pulled a string on the door, and a voice called us to enter. In the center of the single room sat an elderly lady. The room was darkened and smelled of neglect.

The lady was blind or near blind, and almost totally deaf. She was just sitting there, hands on the chair, alone in the dark. As Hammie Lee spoke, she leaned forward, straining to hear him, and then, giving up, lapsed into muttering about her children.

She finally said, “Come tomorrow.” Hammie Lee’s face was sober. He said, “Yes ma’am, yes ma’am,” and we both left very subdued.

The earth smelled sweet, the corn was tall. But at one point I thought I would not be able to go on, and had to force myself to get out of the car.

That night, a group of us stamped letters for a Medicare notice. Afterwards, we drove to the Dairy Maid in the white part of town for a sundae. All of us sat together, laughing, joking and talking in the car.

When we left though, some young white men in a car followed us. They turned up their headlights, yelling obscenities at us through the window at the stoplight. As they tailed us back to our side of town, Louie sat very still in the car and smoked. I jabbered and then was silent. No use pretending.

The superficial approach of canvassing has been bothering me considerably because it does not address the larger issues we run into daily. We finally decided to find out what other concerns the community has in areas like welfare, housing, and public health. Then we will see if we act on it together.

Another new thing is in the air: I asked the kids what activities they would like to do, and they started spouting ideas on every hand—plays, painting, dancing, drawing, and more. So for starters, after lunch Jim C. and I, led by a band of about twenty children, headed for the nearby community center to see if we could use it for some activities. As we walked across the highway to check things out, the children were happily chattering and leaping around in excitement.

The park is not big or even nice. There is broken glass all over, with broken swings and a broken spinning platform. The children didn’t seem to mind and just swarmed all over the equipment, laughing, shouting, and yelling.

I was surprised to see white children playing there too. They were part of a group of about ten white people, led by a heavy-set lady and accompanied by a few teen-agers. “They never talk to us,” said our kids. After a while their group retreated to huddle in the shade of a tree from which they watched us.

Jim went over to them. I played on with our kids, but suddenly it was tense. We didn’t know what would come next. Finally I too went over to the group, and the children followed. Once under the tree together, all the children in our group pressed close to Jim and me, absolutely still and silent.

Jim was talking quietly with the lady:

The lady: “We believe it ain’t Christian to mix them.

Jim: Christ never said that.

The lady: Well, he made them the color they are. Just tell us when you’re going to bring them and we’ll know what to do. We can’t have our children wading in the same pool with them, you understand.

Jim: Ma’am, they have as much a right to wade as your children. And they are simply full of energy and must get it out.

The lady: Stony Hill, down the road, that’s for colored.

Jim: That’s too far, Ma’am.

The lady: Has all the same facilities.

Jim: Have you ever been there?

The lady: No. That’s the colored section. Now this is for white. White people made this and painted it. Just tell us when you’re going to come and we’ll know what to do.

Jim: We can’t stop them, Ma’am.

The lady: (astonished) Well, you brought them here. You brought them here—holding two of them by the hand!

Jim (quietly): It’s a new day.

One of the teenagers muttered: Not until I die.

The lady: We wouldn’t hurt them for the world, see—we just don’t want them around our kids.”

The strange thing is that, when confronted with each other face to face, we were all abashed. All of us. Our two groups sat and talked quietly together. Entrenched, but for a moment at least, speaking. And no one was exploding––no one––from the extended contact.

Our group played quietly a while longer and then left. We must go back.

This afternoon I went canvassing with Hammie Lee J. as my guide. He is thirteen and has a sharp and comic wit. I was glad to be paired with him—my contact, my friend, my guide. We came to a small one-room shack with advertisements hung on the patchwork boarding. We pulled a string on the door, and a voice called us to enter. In the center of the single room sat an elderly lady. The room was darkened and smelled of neglect.

The lady was blind or near blind, and almost totally deaf. She was just sitting there, hands on the chair, alone in the dark. As Hammie Lee spoke, she leaned forward, straining to hear him, and then, giving up, lapsed into muttering about her children.

She finally said, “Come tomorrow.” Hammie Lee’s face was sober. He said, “Yes ma’am, yes ma’am,” and we both left very subdued.

The earth smelled sweet, the corn was tall. But at one point I thought I would not be able to go on, and had to force myself to get out of the car.

That night, a group of us stamped letters for a Medicare notice. Afterwards, we drove to the Dairy Maid in the white part of town for a sundae. All of us sat together, laughing, joking and talking in the car.

When we left though, some young white men in a car followed us. They turned up their headlights, yelling obscenities at us through the window at the stoplight. As they tailed us back to our side of town, Louie sat very still in the car and smoked. I jabbered and then was silent. No use pretending.

July 2, Sumter

|

It thundered and squalled last night. We woke up to rain spitting in our face, what the kids refer to as “dripping rain.”

Today I was paired up with Harold B. one of our Southern university members. We went out into the country for canvassing early in the afternoon after the rain had cleared. We met a blind lady and her ailing sister. They promised to come register. The blind lady carefully repeated all the necessary information and names. “Her memory is good as gold,” said her sister. |

We took refuge at a Kress lunch counter. I got horribly paranoid sitting there. People hanging around outside. Everyone staring. Men in the store, riveting us with their eyes. I thought how much hate must have gone on over this stinking counter. It turns my stomach to go into the white community with friends from the black community. And yet we must do it--to show them it can be done. |

We stopped at Whites and Lilli’s Store, a one-room store full of intriguing jars. The proprietor came out, standing bent-over as he greeted us. He had fine lines around his bright, tired eyes. “My wife just died,” he told us. “I’m ready to close this out. Just come over part of the time.” We’re picking him up Tuesday.

Walking past rows of cornstalks, we saw clouds boiling around the horizon and a deep blue sky going on and on. It was almost peaceful.

A beguiling peace, however. Toni P., one of the white volunteers, reported that the same afternoon she had been driving alone in a nearby area, when her car got trapped in the sand.

An elderly black couple came out to help push. They almost had the car out of the hole when a group of young white men pulled up and parked crossways across the road. At the taunt of “N… Lover,” the frail couple froze, and then faded back into their house.

Toni started to get out of the car, but the young men did too. So she settled back in the car, locked all the doors, and waited them out. After twenty minutes of taunting, they were gone.

Although this did not turn into an incident, it reminded me sharply that among the white volunteers, we have a false sense of security–being as we are a grafted part of the black community. We feel safe in the black part of town, but don’t really understand how deep the divisions run, or even the danger any of us may be facing—or creating––in our encounters with the white community.

It began to rain later in the afternoon just as I had gotten downtown with four of the young girls from our community. We took refuge at a Kress lunch counter in the white part of town. I got horribly paranoid sitting there. People hanging around outside. Everyone staring. Men in the store, riveting us with their eyes.

I thought how much hate must have gone on over this stinking counter.

It turns my stomach.

We came home, sopped. It was beating down rain, and I was grateful for nature’s interference.

It makes me wonder what good we volunteers can do here for such a short amount of time. Soon we too will melt back into our own communities, leaving this essential ugliness and confrontation, no matter how good our intentions. And yet we must keep going, if only to show that it can be done.

Walking past rows of cornstalks, we saw clouds boiling around the horizon and a deep blue sky going on and on. It was almost peaceful.

A beguiling peace, however. Toni P., one of the white volunteers, reported that the same afternoon she had been driving alone in a nearby area, when her car got trapped in the sand.

An elderly black couple came out to help push. They almost had the car out of the hole when a group of young white men pulled up and parked crossways across the road. At the taunt of “N… Lover,” the frail couple froze, and then faded back into their house.

Toni started to get out of the car, but the young men did too. So she settled back in the car, locked all the doors, and waited them out. After twenty minutes of taunting, they were gone.

Although this did not turn into an incident, it reminded me sharply that among the white volunteers, we have a false sense of security–being as we are a grafted part of the black community. We feel safe in the black part of town, but don’t really understand how deep the divisions run, or even the danger any of us may be facing—or creating––in our encounters with the white community.

It began to rain later in the afternoon just as I had gotten downtown with four of the young girls from our community. We took refuge at a Kress lunch counter in the white part of town. I got horribly paranoid sitting there. People hanging around outside. Everyone staring. Men in the store, riveting us with their eyes.

I thought how much hate must have gone on over this stinking counter.

It turns my stomach.

We came home, sopped. It was beating down rain, and I was grateful for nature’s interference.

It makes me wonder what good we volunteers can do here for such a short amount of time. Soon we too will melt back into our own communities, leaving this essential ugliness and confrontation, no matter how good our intentions. And yet we must keep going, if only to show that it can be done.

July 3, Sumter

Today was communion Sunday at Mount Pisgah and a group of us went to hear Rev. James give his sermon. The church sang with full heart:

Precious Lord, take my hand,

Lead me on, let me stand,

I am tired I am weak, I am worn

Thru the storm, thru the night,

Lead me on to the light,

Take my hand precious Lord,

Lead me home.

Back at the parsonage, we had a big Sunday dinner of hash and corn, and then prepared for our community meeting. We had invited people from our canvassing visits to come discuss problems they see in the community. Eventually, six people showed. At first, the talk was very constricted, and people felt uneasy. But as we defined a few more of the local problems and got some contacts, it ended with all of us feeling fairly enthusiastic about the possibility of getting something started.

Precious Lord, take my hand,

Lead me on, let me stand,

I am tired I am weak, I am worn

Thru the storm, thru the night,

Lead me on to the light,

Take my hand precious Lord,

Lead me home.

Back at the parsonage, we had a big Sunday dinner of hash and corn, and then prepared for our community meeting. We had invited people from our canvassing visits to come discuss problems they see in the community. Eventually, six people showed. At first, the talk was very constricted, and people felt uneasy. But as we defined a few more of the local problems and got some contacts, it ended with all of us feeling fairly enthusiastic about the possibility of getting something started.

July 4, Poinsett State Park

|

Rise and shine everyone! We woke at 7:30 am, eager to head out for our July 4 picnic at Poinsett State Park––a place miles from Sumter where we could all relax as a mixed group. And we really needed a break. We waited impatiently till we finally got off at 11:00 am. Our frustration dissolved as soon as we got moving, and we were in high spirits as we rolled past rich red dirt and piney woods.

Once at the park, we put blankets on the grass and had a picnic of spareribs, baked beans, and potato salad. We canoed in the lake, and then started a high-energy baseball game. In the middle of the game, about 10 young black guys from another group came over and asked to join us. All of us played hard and happy. |

|

Harold and I got into a water fight at the end of the day, and ran squirting each other all around the field. “The looks you got!” said Margaret. It was a wonderful day. We wished it could continue.

July 5, Sumter

|

We were posted as poll-watchers at the Registration Board all day today. Everything went pretty smoothly. But in expectation of us they had posted signs advising registrants to “Please! Enter by side door.”

As poll-watchers we weren’t allowed to go inside, but we would confer with the people we brought as they came out, sending them back in if needed. A few were refused because they couldn’t subtract their ages to get a birth date, a few others because they couldn’t remember birthdays. Very few were totally turned away. |

I was delighted to see 80-year old Mary Davis arrive in a car. Smiling broadly, she said “They came out to the car to register me. Ah yes, I was so happy!” Another lady, holding up her registration card, said to us with a big smile, “I’m not going to lose this for anything!” |

I was delighted to see 80-year old Mary Davis arrive in a car. Smiling broadly, she said, “They came out to the car to register me. Oh yes, I was so happy!” Another lady, holding up her registration card, said to us with a big smile, “I’m not going to lose this for anything!”

At the end of the day, we saw 73 people registered.

At the end of the day, we saw 73 people registered.

While we were waiting there, an elderly white man came up. He was quaky and thin as a reed. I thought he would blow over. He wanted to know where Medicare was. I felt sorry for him.

We sent him over to one of our cars where one of our drivers sat with a lady who had just registered. I saw the driver glaring suspiciously behind the wheel as the white man approached, and hoped they would work it out. Yes, he got in the car all right, and off they went to drop him at the Medicare office.

That evening, there was an NAACP meeting about Medicare. Tuomey Hospital in Sumter won’t comply with the Federal standards and so does not qualify for Medicare reimbursements. This cuts across black and white lines. Could this be an issue for community cooperation?

We sent him over to one of our cars where one of our drivers sat with a lady who had just registered. I saw the driver glaring suspiciously behind the wheel as the white man approached, and hoped they would work it out. Yes, he got in the car all right, and off they went to drop him at the Medicare office.

That evening, there was an NAACP meeting about Medicare. Tuomey Hospital in Sumter won’t comply with the Federal standards and so does not qualify for Medicare reimbursements. This cuts across black and white lines. Could this be an issue for community cooperation?

July 6, Sumter

This afternoon, a company of us dispatched ourselves to the tracks for canvassing. By the end of our shift, we were hot and sweaty and dirty. At every turn, people would say, “Come in and sit down. It’s hot to be walking around like that.”

One lady we met was washing clothes in a tub. She was very suspicious, but then we got to talking—or rather listening. Her husband had been shot. Salvation Army kept her kids in clothes. Two of the seven have gone to school, and these two little ones running around were her grandchildren. She kept spitting blood through her teeth, aiming at various corners of the yard. She didn’t want to talk about registering. Life had already been too hard.

We got 87 names on the books today.

One lady we met was washing clothes in a tub. She was very suspicious, but then we got to talking—or rather listening. Her husband had been shot. Salvation Army kept her kids in clothes. Two of the seven have gone to school, and these two little ones running around were her grandchildren. She kept spitting blood through her teeth, aiming at various corners of the yard. She didn’t want to talk about registering. Life had already been too hard.

We got 87 names on the books today.

July 7, Sumter: Last day of registration for this registration period

|

Last day of registration for this registration period.

This morning I got an unexpected letter from my father. He had been out of the country with his second wife when I left to join the project. It said: “Get your ass on home in twenty-four hours or I’ll take your mother to court.” I sat stunned and unbelieving. Toni came in and looking at my face, sat down. “Is it a death?” she asked. Suddenly I was embarrassed for considering myself indispensable, but also angry for having wasted time that was so precious. “No,” I said, then had to force myself to add, “thank God.” |

But it did feel like a death. I have become so deeply attached to this project, and to every single person I have met. I have never been so totally committed to anything in my life...I lay awake thinking for a long time, and recalled my earlier fears about the “raw-boned reality” I was coming to meet. I realized that in my short time here I have not experienced any real hate--I have mainly seen a lot of love. |

But it did feel like a death. I have become so deeply attached to this project, and to every single person I have met. I have never been so totally committed to anything in my life.

I sat staring out the window--Toni simply there, waiting. I saw bicycles go by, a little boy walk underneath. I felt the place started reeling away from me, almost a physical sensation, as I tried to gather my guts and prepare for disengaging my heart. A strange nightmare––dizzy and unreal.

I broke the news to our project leaders but not yet to any of the other members in our group. I wanted to see the last day through on my own. So I made a few calls, sent a telegram, and then went out to do my shift at the Registration Board. I sat there boiling in the sun, sweating grimly and gladly. Every person was a light to me, every face a victory.

I sat until 5:00 pm and when all was told, we had 106 names registered for the day. We were all excited, but I was ecstatic––so grateful that if indeed I had to leave, I had seen at least this one small thing through.

So that is how I got through the day––by not talking, by wanting to see everything going on as usual—and just taking in every precious moment.

Tonight was the talent show rehearsal. This was the one activity I had been planning with the neighborhood children, and it was happening now at last.

At the hint of activity, they appeared from nowhere--Linda, Betty, Patricia, Janie, Barbara Jean, Yvonne, Yvette, Anabelle, Rosalie, Bertie, Celestine, Julie, Hammie Lee, Malachi, James, Bernard, Thomas, Jimmie, Robert Lee. They were milling around now.

I couldn’t stop hugging them.

The rehearsal degenerated painlessly into a dance and a great release of energy. Gay J. and I took two of them, Patricia and Barbara Jean, into the dark dining room to continue “planning,” but their young heads kept turning wistfully towards the sounds of the dance.

It is the children that I am most torn to leave. I will never forget them waving and calling at me, “Abby! Is Abby there? Abby, here is my record to play. Will you be Treasurer of the Talent Show? Do ushers wear black? I want to draw, I want to dance. Can I play the guitar?”

Toni and I didn’t talk much that night before bed, just good-night. “We’ll miss you,” she said. “I’ll miss you too.”

I lay awake thinking for a long time. I recalled my earlier fears about the “raw-boned reality” I was coming to meet. I realized that in my short time here I have been deeply changed—not so much by the hate and the fear, but by witnessing so much courage and love.

I sat staring out the window--Toni simply there, waiting. I saw bicycles go by, a little boy walk underneath. I felt the place started reeling away from me, almost a physical sensation, as I tried to gather my guts and prepare for disengaging my heart. A strange nightmare––dizzy and unreal.

I broke the news to our project leaders but not yet to any of the other members in our group. I wanted to see the last day through on my own. So I made a few calls, sent a telegram, and then went out to do my shift at the Registration Board. I sat there boiling in the sun, sweating grimly and gladly. Every person was a light to me, every face a victory.

I sat until 5:00 pm and when all was told, we had 106 names registered for the day. We were all excited, but I was ecstatic––so grateful that if indeed I had to leave, I had seen at least this one small thing through.

So that is how I got through the day––by not talking, by wanting to see everything going on as usual—and just taking in every precious moment.

Tonight was the talent show rehearsal. This was the one activity I had been planning with the neighborhood children, and it was happening now at last.

At the hint of activity, they appeared from nowhere--Linda, Betty, Patricia, Janie, Barbara Jean, Yvonne, Yvette, Anabelle, Rosalie, Bertie, Celestine, Julie, Hammie Lee, Malachi, James, Bernard, Thomas, Jimmie, Robert Lee. They were milling around now.

I couldn’t stop hugging them.

The rehearsal degenerated painlessly into a dance and a great release of energy. Gay J. and I took two of them, Patricia and Barbara Jean, into the dark dining room to continue “planning,” but their young heads kept turning wistfully towards the sounds of the dance.

It is the children that I am most torn to leave. I will never forget them waving and calling at me, “Abby! Is Abby there? Abby, here is my record to play. Will you be Treasurer of the Talent Show? Do ushers wear black? I want to draw, I want to dance. Can I play the guitar?”

Toni and I didn’t talk much that night before bed, just good-night. “We’ll miss you,” she said. “I’ll miss you too.”

I lay awake thinking for a long time. I recalled my earlier fears about the “raw-boned reality” I was coming to meet. I realized that in my short time here I have been deeply changed—not so much by the hate and the fear, but by witnessing so much courage and love.

July 8, Sumter

At this morning’s meeting, we celebrated the final registration tally. In the three-day open registration period from July 5-7, we had registered a total of 266 voters. Now we will divide up into action groups to handle other community issues--citizenship education, slum lords, electricity and plumbing, education, and welfare. So everything is finally take shape.

Then I had the floor. Smoking fiendishly, and with much difficulty, I told them all my news. Everyone was very silent.

I left right after with Atty. Finney for Washington D.C. and the airport.

I’ll be back.

Then I had the floor. Smoking fiendishly, and with much difficulty, I told them all my news. Everyone was very silent.

I left right after with Atty. Finney for Washington D.C. and the airport.

I’ll be back.